i submitted this for my first operating system homework at starfleet academy. scotty gave me a poor grade on it because he said this is exploitable.

rtooos.quals2019.oooverflow.io 5000(Solves: 30, 143 pts)

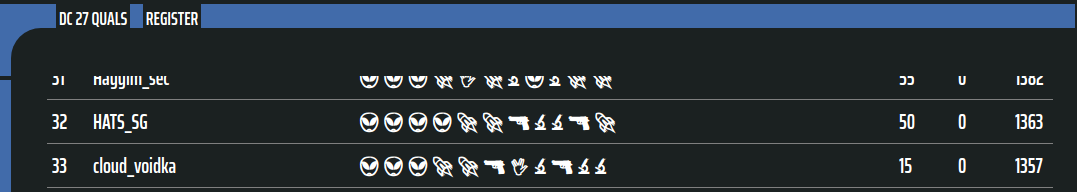

This weekend I got together with my team HATS SG for the annual DEF CON CTF Qualifier. I was primarily the one working on pwns in this CTF, and I managed to solve some of the speedruns, babyheap and this challenge. I thought this challenge was pretty cool so I’m writing up on it.

Overview

We are only provided with a binary called crux, and a remote server to connect to. At a first look, I can’t tell what kind of file crux should be.

lord_idiot:~/CTF/defcon19/RTOoOS$ file crux_7377a1f43e35924971ef1b172c080e03131bed56

crux_7377a1f43e35924971ef1b172c080e03131bed56: dataSo I just connect to the remote service with netcat and I’m presented with the following shell-like interface.

CS420 - Homework 1

Student: Kurt Mandl

Submission Stardate 37357.84908798814

[RTOoOS>

Therefore, it is quite obvious that crux should be executable in some form. So I throw it in IDA and it analyses the binary quite properly, so I assume that 64-bit is the correct architecture. Taking the address 0 to be the entry-point, it is just a bit of effort to work through and reverse the binary.

The binary implements a few features similar to bash, which are help, ls, id, cat, export, unset, env. What’s interesting about this binary though is that it doesn’t call libc functions like system or write, and it doesn’t seem to make any syscalls. Rather, everything seems to interact with I/O ports through the out instruction. For example, the print function looked like so.

seg000:0000000000000076 ; __int64 __fastcall print(char *buf)

seg000:0000000000000076 print proc near ; CODE XREF: parse_cmd+82p

seg000:0000000000000076 ; parse_cmd+D7p ...

seg000:0000000000000076 mov rax, rdi

seg000:0000000000000079 mov edi, 64h ; 'd'

seg000:000000000000007E out dx, al

seg000:000000000000007F retn

seg000:000000000000007F print endp

Having done a few VM and hypervisor challenges in the past, this behaviour looks similar to how one could implement hypercalls to a hypervisor watching the execution. What makes it most obvious that this is interacting with a hypervisor is the fact that the out dx, al instruction only sends 1 byte to the I/O port, and yet one call to print prints out the whole string that rdi points to in memory. This indicates that the hypervisor is watching for the out instruction, then reading the register values at the point of the instruction, and performing the relevant functionality like printing to screen.

Kernel-land

The first thing we have to do is pwn the crux binary. We have to find some way to achieve shellcode execution, as our first goal is to read the hypervisor code, but the cat functionality provided prevents us from doing so.

if ( !strncmp("cat ", cmd, v7) )

{

if ( strlen(cmd) <= 4 )

{

v45 = 0;

v9 = print("no file to cat", (__int64)cmd, v8);

return v45;

}

if ( strstr(cmd + 4, "honcho") )

v11 = print("reading hypervisor blocked by kernel!!", (__int64)"honcho", v10);

else

v12 = print_file(cmd + 4, (__int64)"honcho", v10);

}This means that unless we can find some way to bypass these checks, we’ll have to get arbitrary shellcode execution in order to manually print out the honcho file. The bug that allows for this is present in the export functionality, which allows us to define environment variables as key:value pairs. I suggest you take a look at reversing this functionality on your own, as there are some details I will be omitting for brevity. Essentially, when a user defines a new environment variable like so:

export key=value

It will store this key in the first empty slot in an array of buffers at 0x1650. If this key has been defined before, then it will read the value into a buffer that is determined by getting the pointer from a parallel array of pointers char *val_arr[] at 0x4650. If this key is new, then the corresponding val_arr does not have a pointer yet, so the custom malloc function will be called to allocate some memory to use as the buffer for val.

This custom malloc function is relatively simple. The heap starts at 0x3650 with 1 chunk of 0x1000 size. Each chunk has the following structure, with metadata at the beginning, and with a variable size contents.

00000000 chunk struc ; (sizeof=0x20, mappedto_2)

00000000 ; XREF: some_data:some_global/r

00000000 size dq ?

00000008 is_avail dd ?

0000000C field_C dd ?

00000010 next dq ? ; offset

00000018 contents db 8 dup(?)

00000020 chunk ends

Upon an allocation, it will search through the existing chunks (there is only 1 in the beginning), to look for chunks which are available(is_avail) with size larger than or equal to the allocation size with metadata. If such a chunk is found, it will be split exactly to the allocation size required, and leaving the remainder for use later. Therefore, the allocation looks something like this.

[chunk A (0x1000)]*

malloc(0x100-0x18);

[chunk A (0x100)] [chunk B (0xf00)]*

* = is_avail

The bug then lies in the implementation of variable expansions in export. The functionality allows for expansion when exporting an environment variable. This is best explained by example.

CS420 - Homework 1

Student: Kurt Mandl

Submission Stardate 37357.84908798814

[RTOoOS> export a=is cool

[RTOoOS> export b=Lord_Idiot $a

[RTOoOS> env

a=is cool

b=Lord_Idiot is cool

What you’ll notice when you reverse the implementation of this behaviour is that while you cannot send more input than the allocated size for the value array, size checks are not done with variable expansions, thus you can write more data than the chunk can fit if the variable that is expanded is large. In the following example, the b chunk will be overflowed using data from a

CS420 - Homework 1

Student: Kurt Mandl

Submission Stardate 37357.84908798814

[RTOoOS> export a=AAAAA ... AAA (400 "A"s)

[RTOoOS> export b=BBBBB ... BBB$a (400 "B"s)

The exploitation of this is thus quite straightforward. If we overflow the chunk into the size member of the next chunk, we can make the allocator believe that this chunk is larger than it is. This allows us to make allocations beyond the initial 0x1000 memory space. What you’ll then notice is that the heap area (0x3650) is placed right before the array of pointers val_arr[] (0x4650). We can thus transform our buffer overflow into a arbitrary read and write by overwriting these pointers.

By overwriting these pointers with addresses in executable memory. We can leverage export to write into executable memory, allowing us to have arbitrary shellcode execution! With this arbitrary shellcode execution, we mimic the cat hypercall and dump the hypervisor code, honcho.

Hypervisor-land

Upon dumping the hypervisor, we realise that it is a Mach-O binary (gasps)

lord_idiot:~/CTF/defcon19/RTOoOS$ file hypervisor

hypervisor: Mach-O 64-bit x86_64 executableThis is the executable format that MacOS uses, which is tragic since I run linux. Just like the kernel-land exploit, I’m going to have to exploit this without much debugging as I can only test the program through the remote server.

There’s a bunch of stuff going on in this binary, but it was getting very late into the night and I had school the next day, so I tried to reverse this as fast a possible. A good trick to use usually to pinpoint the areas to reverse is to just find important strings, then find the cross-references (xrefs) to them. This lands me in the hypervise function, which amongst other things handles the hypercalls I had mentioned earlier. Zooming straight into the hypercalls, you will notice that the hypervisor prevents you from reading any file with the string “flag” in it.

case 0x66LL:

filename = &vm_mem[_rax];

if ( strcasestr(&vm_mem[_rax], "flag") )

{

printf("hypervisor blocked read of %s\n", filename);

}

else

{

fileptr = ReadFile(0LL, filename, (__int64 *)&sz);

write(1, fileptr, sz);

}You will also notice that the read and write hypercalls are not implemented with adequate checking.

case 0x63LL:

v9 = read(0, &vm_mem[_rax], _rsi);

hv_vcpu_write_register((unsigned int)vcpu, 2LL, v9);

break;

case 0x64LL:

puts(&vm_mem[_rax]);

break;These hypercalls do not perform bounds checking on the value of rax. This means that we have an Out-of-Bounds (OOB) read and write primitive! So how can we use this to read our flag? Using xrefs to find where vm_mem was initalised, you can see that is was allocated by valloc

int map_memory()

{

char *v0; // rax@1

__int64 v1; // rbx@1

v0 = (char *)valloc(0x400000uLL);

v1 = (__int64)v0;

vm_mem = v0;

__bzero(v0, 0x400000LL);

return hv_vm_map(v1, 0LL, 0x400000LL, 7LL);

}As far as I know, valloc just allocates memory aligned to the page boundary, just like mmap would. At this point, daniellimws and I were pretty stuck. Although we have an OOB read and write, we do not know the address returned by valloc as it is not constant, neither do we know the binary base as the hypervisor binary has PIE enabled, so it is mapped to a different location everytime.

Lucky for us, daniel has a Mac 🍏. So we ran the hypervisor, and tried to observe the memory mappings. What he noticed was that the offset between the PIE base and the allocated vm_mem was constant! This allows us to exploit the OOB with no problem. One issue though is that while the offset is constant, the value is different in remote and local, so we had to bruteforce to find the exact offset. Afterwards, the exploitation was rather straightforward

All we had to do was make sure that the strcasestr in the cat hypercall returns 0, allowing us to read the file. We can do this by replacing the Global Offset Table (GOT) entry of strcasestr with a function that will return 0 with our arguments. We chose to use atoi. Thus, the exploitation goes like so (in pseudocode).

atoi_addr = OOB_read(atoi_GOT)

OOB_write(strcasestr_GOT, atoi_addr)

cat_hypercall("flag")

With this, we get our flag!

OOO{wow hypervision on apple}

Defcon thoughts

This was the first time I’ve played a DEF CON CTF Qualifier, and my team placed 32nd on the overall scoreboard, and 14th on the speedrun scoreboard. I was hoping to qualify for the finals, but I guess we aren’t at that level yet. It’s a bit disappointing but I guess we’ll have to try again next year :P