nc stack.overflow.fail 9001

by hk (Solves: 7, 1150 pts)

This weekend I played with WreckTheLine in 3 CTFs \(X_X)/, AeroCTF, Pragyan CTF and UTCTF. I’m really proud because we performed really well for them, finishing 19th, 3rd and 1st(!) respectively. The challenges in UTCTF were a lot more fun than I had expected. I managed to solve most of the pwns, except for Jendy’s(which our resident pwn expert NextLine solved), and solved ECHO together with the team. I had most fun with the PowerPC challenge in particular. When I saw the challenge, I thought it was a perfect opportunity to learn a new architecture and a new tool that would be useful for this challenge (Ghidra).

Power of PC

So far I’ve only ever done x86 challenges, never trying challenges from other architectures like ARM, PowerPC etc. By no means am I a PowerPC expert (or even an amateur), but heres some things I’ve learnt about PowerPC64 over the weekend as I attempted to solve this foreign challenge.

Registers

Similar to ARM, PowerPC has a massive number of registers. Fortunately, the register usage in PowerPC64 seems to be pretty similar to x86, so we don’t have too much of an issue. Here is a table of registers and their short descriptions that I made during the CTF.

|______________|__PowerPC Reg__|__________Description__________|___x86 equiv___|

|GPR (General) | r1 | Stack pointer | rsp |

| | r2 | System-reserved | ? |

| | r3-r4 | Parameter passing/Return val | rdi/rsi/rax |

| | r5-r10 | Parameter passing | rdx ... r9 |

| | r11-r12 | Wo bu zhi dao | ? |

| | r13 | small data area pointer (???) | ??? |

| | r14-r30 | Local vars | * |

| | r31 | Local var/Environment pointers| ? |

|______________|_______________|_______________________________|_______________|

|SPR (Special) | LR | Link register, saves IP | _ |

| | CR | Condition register | EFLAGS |

| | CTR | Count register, loop count | rcx |

| | XER | Fixed-point exception register| ? |

| | FPSCR | Floating-point status and .? | ? |

|______________|_______________|_______________________________|_______________|

This is obviously not a comprehensive list, but it is roughly accurate enough to give you an idea of what kind of registers exist in PowerPC. After spending some time reversing the PowerPC binary, their uses may become a bit more clear.

Calling convention

This part tripped me up the most while doing the challenge. The calling convention of PowerPC is rather different from x86, which requires a bit more mental gymnastics for me to wrap my x86 head around. After reading a pretty useful reference, I was able to get a better idea. But what I found most effective was looking at the function prologues and epilogues in the binary, which gave me a good idea of how the calling convention works.

Here is what the stack will look like from the caller.

Low addresses (top of stack) ________________

________________ |______Code______|

| |<- r1 ....

| Linkage area | 0: bl callee <- IP

|________________| 4: ....

| | 8: ....

| Parameter area |

|________________|

High addresses

The bl instruction will branch, which is like a call in x86. However, instead of pushing the address of the next instruction (4) onto the stack like in x86, in PowerPC, the address of the next instruction will be contained in the link register(LR). Now, the function prologue of the callee will setup the stack for it’s own stack frame, and set up for the function to return back to the caller properly.

Low addresses (top of stack) ________________ _______________

________________ |______Code______| |___Registers___|

| |<- r1 .... ...

| 4 | 1000: mfspr r0, LR < LR: 0x4

|________________| 1004: std r0, 0x10(r1) <- IP r0: 0x4

| | 1008: .... r1: 0x100

| Parameter area |

|________________|

High addresses

As can be seen here, the value of the link register(4) will be moved into r0. The value of r0 is then stored into the linkage area of the caller’s stack, since r1 has not been changed yet. Now that the address to return to is stored, the callee prologue will setup it’s own stack frame.

Low addresses (top of stack) ________________ _______________

________________ |______Code______| |___Registers___|

| |<- r1 .... ...

| Callee stack | 1014: stdu r1, -0x30(r1) < r1: 0xd0

|________________| 1018: or r31, r1, r1 <- IP r31: 0xd0

| | 101c: ....

| 4 |

|________________|

| |

| Parameter area |

|________________|

High addresses

To setup it’s own stack frame, the callee will decrease the stack pointer r1 by the number of bytes required for it’s own variables, parameters for any function it will call, and it’s own link area. r31 is also set to the value of r1, so it can act as a stack pointer too.

Low addresses (top of stack) ________________ _______________

________________ |______Code______| |___Registers___|

| |<- r1 .... ...

| 4 | 10f0: addi r1, r31, 0x30 < LR: 0x4

|________________| 10f4: ld r0, 0x10(r1) < r0: 0x4

| | 10f8: mtspr LR, r0 < r1: 0x100

| Parameter area | 10fc: blr <- IP r31: 0xd0

|________________| 1100: ....

High addresses

When the callee has finished execution. The function epilogue will proceed to increase the stack pointer r1 by 0x30 to get rid of the callee stack. Then, r0 will load the saved address in the linkage area of the caller. The link register LR is set to the value of r0. Afterwards, the blr instruction will cause program execution to jump to the address of LR, which is what was saved on the stack earlier (4 in this case). Now the caller’s execution will continue.

Challenge begins

Now that the prerequisite knowledge for PowerPC has been covered. The exploitation of the challenge binary begins. Since this challenge was in PowerPC, I wanted to try out the decompiler of Ghidra, to see how well it can help me in this challenge. And I was pleasantly surprised by how helpful Ghidra was in this challenge. Here is the decompiled main of the challenge binary.

void main(void)

{

size_t len;

size_t __edflag;

int i;

/* local function entry for global function main at 10000a78 */

welcome();

get_input();

len = .strlen(buf);

i = 0;

while (i < (int)len) {

buf[(longlong)i] = buf[(longlong)i] ^ 0xcb;

i = i + 1;

}

__edflag = len;

__printf(0x1009ed68,(longlong)(int)len);

.encrypt((char *)(longlong)(int)len,__edflag);

.puts("Exiting..");

/* WARNING: Subroutine does not return */

.exit(1);

}The get_input() function first reads 1000 bytes from the user into a global buffer buf. The amount of input we sent is determined using strlen(), and then our input is xor’d with the constant 0xcb. The bug of this challenge is found in the encrypt function that is later called.

void .encrypt(char *_local_88,int __edflag)

{

undefined1 *puVar1;

int i;

char local_88 [104];

/* local function entry for global function encrypt at 10000bb4 */

puVar1 = buf;

.memcpy(local_88,buf,1000);

/* heres your string */

__printf(0x1009ede0,puVar1);

i = 0;

while (i < 0x32) {

__printf(0x1009edf8,(longlong)(int)(uint)(byte)local_88[(longlong)i]);

i = i + 1;

}

.putchar(10);

return;

}As you can see, the memcpy(local_88, buf, 1000) will cause a gigantic buffer overflow, since local_88 only holds space for 104 bytes. So how can we exploit this?

Back to classics

This looks like a classic buffer overflow challenge, just with a twist that it is in a PowerPC binary. So let’s apply what we’ve learnt earlier to solve this challenge. Now first thing’s first, whatever payload we send is going to be xor’d with the constant 0xcb. So we are going to have to work around this. There are two options. Firstly, we can xor our payload with 0xcb before sending it over. When it is xor’d again inside the binary, we get back our original payload. This is based on the basic xor principle of something.

(A ^ B) ^ B == A

Alternatively, we can send a null byte at the start of our payload. This will cause strlen to return 0, so the for loop of the xor cipher will not even run. This is what I did.

Now that that is out of the way, we can get to exploiting the buffer overflow. If you’ve understood the earlier explanation of the calling convention in PowerPC, you can see that the address that a function will return to is stored below the function’s stack frame. With a buffer overflow, we can easily overwrite this address to something else, allowing us to have IP control! This is very similar to exploitation in x86.

Low addresses (top of stack)

________________ ________________

| |<- r1 | |<- r1

| Callee stack | | AAAAAAAAAAA.. |

|________________| |________________|

| | | |

| Saved ret addr | | AAAAAAAAAAA.. | (overwritten!)

|________________| |________________|

| | | |

| Parameter area | | Parameter area |

|________________| |________________|

High addresses

Rop Rop Rop Rop

In a x86 challenge with a buffer overflow, we always do return-oriented programming (ROP) to gain a shell. It’s the same here. However, there is a difference, since PowerPC does not have a ret instruction that pops of from the stack. Instead, we need to find gadgets that set the value of the link register LR from a value on the stack. Then the gadget should end with a blr instruction which jumps to the address in LR. Just with any other binary, I threw the challenge into ropper to find the gadgets we need!

lord_idiot:~/CTF/utctf19/PPower_enCryption$ ropper --file ppc

Please report this error on https://github.com/sashs/ropper

Stacktrace:

...

RopperError: [REDACTED]oof.

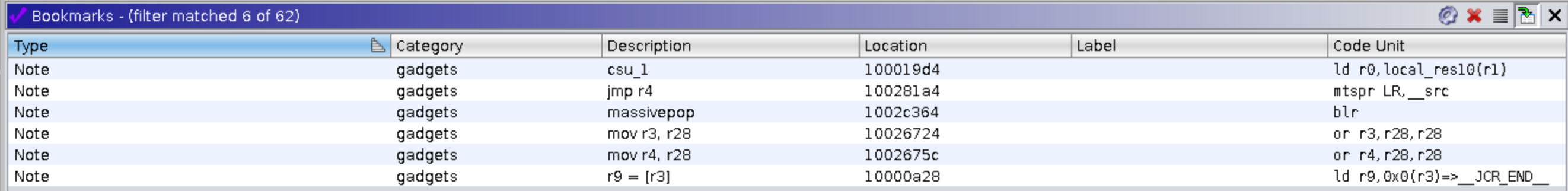

Seems we’re going to have to find our gadgets. How can we do this? I decided to mess around in Ghidra, to learn more about it’s capabilities. That’s when I found this really useful feature, Search > For Matching Instructions. What this feature does is that it allows for us to select an existing instruction, and to find similar instructions in the rest of the binary. To give an example, if we had the instruction ld r0, 0x10(r1), we could search for many similar variants.

ld r0, 0x10(r1)

ld r*, 0x10(r1)

ld r0, *(r1)

ld *, *(*)

...

I found this feature really powerful and useful when looking for rop gadgets. To search for “pop” gadgets, I searched for ld r*, *(r1), such gadgets would load a value from the stack into the register. Going through a few of them yielded many very useful gadgets. To save the gadgets, I bookmarked them in Ghidra using the Bookmark feature, and categorised them together as “gadgets”.

To make sure they were usable gadgets, I checked if they would eventually set the value of LR to something that is present on the stack, and then blr to jump to that address. If there wasn’t such an instruction in the gadget, the gadget would not be chainable, thus pretty useless for our needs.

TITLE_PLACEHOLDER

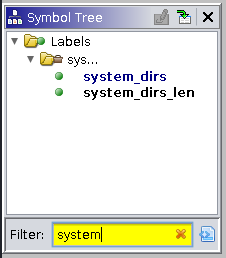

Now we roughly know how to find the gadgets we need in Ghidra, so what should our ROP chain look like? A quick search using the symbol tree shows that we don’t have system or any exec variant in the statically linked challenge binary.

In such a situation, ropping all the way to a shell might become more difficult. A useful technique would be to stage our attack. Rather than aiming to rop straight to popping a shell, we can try writing a ROP chain that allows us to jump to shellcode instead! Let’s check if there are any exectuable AND writable sections in the challenge.

lord_idiot:~/CTF/utctf19/PPower_enCryption$ readelf ppc -lW

Elf file type is EXEC (Executable file)

Entry point 0x10000840

There are 6 program headers, starting at offset 64

Program Headers:

Type Offset VirtAddr PhysAddr FileSiz MemSiz Flg Align

LOAD 0x000000 0x0000000010000000 0x0000000010000000 0x0b7ad6 0x0b7ad6 R E 0x10000

LOAD 0x0be490 0x00000000100ce490 0x00000000100ce490 0x003588 0x005130 RW 0x10000

NOTE 0x000190 0x0000000010000190 0x0000000010000190 0x000044 0x000044 R 0x4

TLS 0x0be490 0x00000000100ce490 0x00000000100ce490 0x000020 0x000054 R 0x8

GNU_STACK 0x000000 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 0x000000 0x000000 RWE 0x10

GNU_RELRO 0x0be490 0x00000000100ce490 0x00000000100ce490 0x001b70 0x001b70 R 0x1GNU_STACK ... RWE. Perfect! We have an executable stack. Therefore, we can write PowerPC shellcode on the stack to pop a shell, then find a gadget that allows us to jump to the stack.

However, finding such a gadget turned out to be harder than I thought, as I could not find gadgets that moved the value of r1 eventually into the link register LR. This makes sense since there would basically never be a case where a normal binary needs to jump into the stack.

When in doubt, csu_init

I found the solution to my problem in a familiar gadget that I love to use in x86. The beloved __libc_csu_init gadget! Luckily for us, this PowerPC binary also had the __libc_csu_init gadget. The key to using this gadget is the following instructions.

100019a0 09 00 3e e9 ldu r9,0x8(r30)

...

100019b8 a6 03 29 7d mtspr CTR,r9

...

100019c0 21 04 80 4e bctrl

The ldu instruction will dereference r30+0x8 and put the qword into r9. In x86, this is equivalent to mov r9, qword ptr[r30+0x8]. The value of r9 is then loaded into CTR, and bctrl will jump to the address in CTR. If we control the value of r30 this gadget can be really powerful! Luckily for us, __libc_csu_init handles that too.

100019d4 10 00 01 e8 ld r0,local_res10(r1)

...

100019e8 f0 ff c1 eb ld r30,local_10(r1)

...

100019f0 a6 03 08 7c mtspr LR,r0

100019f4 20 00 80 4e blr

With this other gadget, we are able to control our return address (so it’s chainable), and we also set the value of r30 from a value on the stack.

With these two gadgets chained together, we can jump to the stack if we have a known address that contains a pointer to the stack. This would be the .bss section of our binary. The section is always mapped to the same address since PIE is not enabled, so we just need to find where the pointers are. I did this using a feature added to the gef command scan by my friend daniellimws.

gef➤ vmmap

Start End Offset Perm Path

... (this is the .bss)

0x00000000100ce000 0x00000000100d2000 0x00000000000be000 rw- /home/lord_idiot/CTF/utctf19/PPower_enCryption/ppc

0x00000000100d2000 0x00000000100f6000 0x0000000000000000 rw-

... (this is the stack)

0x0000004000001000 0x0000004000801000 0x0000000000000000 rw-

...

gef➤ scan 0x00000000100d2000-0x00000000100f6000 0x00000040007ff000-0x0000004000800000

[+] Searching for addresses in '0x00000000100d2000-0x00000000100f6000' that point to '0x00000040007ff000-0x0000004000800000'

0x00000000100d2498│+0x0498: 0x00000040007ffb78 → 0x00000040007fff44 → "XDG_SEAT=seat0"

0x00000000100d33f0│+0x13f0: 0x00000040007ffdc8 → 0x0000000000000016

0x00000000100d3490│+0x1490: 0x00000040007ffb68 → 0x00000040007fff3e → 0x4458006370702f2e ("./ppc"?)

0x00000000100d4100│+0x2100: 0x00000040007ff7e0 → 0x7822847c48006138 ("8a"?)

The final address 0x00000000100d4100 was the magic address, as the stack pointer it had (0x00000040007ff7e0) fell within the 1000 byte buffer overflow we had in the stack. So I just had to make sure that my shellcode ended up in this area.

Chaining everything together (I’ll leave the shellcode writing as an exercise for the reader), we get our ROP chain that jumps to the shellcode that pops our shell!

utflag{why_th3_fuck_c@n_i_0nly_put_16_b1ts_@t_@_t1m3}

mtspr LR, r0; blr

The journey to solving this challenge was really fun for me, and now I’m a bit more familiar with PowerPC and Ghidra. I think this tool is actually really cool, and I’m loving that it’s able to decompile all sorts of weird architectures (even if it isn’t a perfect decompile). Also, I’m pretty proud that after struggling through this challenge, I was able to solve this challenge in second place, about 2 hours slower than the first blood team.

Since Ghidra was pretty useful for solving this challenge, I also decided to give it a quick makeover!