behold my collection

The container is built with the following important statements

FROM ubuntu:18.04 RUN apt-get -y install python3.6 COPY build/lib.linux-x86_64-3.6/Collection.cpython-36m-x86_64-linux-gnu.so /usr/local/lib/python3.6/dist-packages/Collection.cpython-36m-x86_64-linux-gnu.so Copy the library in the same destination path and check that it works with

python3.6 test.py Challenge runs at 35.207.157.79:4444

Difficulty: easy (Solves: 30, 150 pts)

Disclaimer: I didn’t manage to solve this during the CTF, but I still enjoyed the challenge and so I decided to write a writeup after solving it. Also this basically ate up 2 days of my life so I must as well document it.

Overview

This challenge provides us with some files. The important ones are python3.6 and Collection.cpython-36m-x86_64-linux-gnu.so. As you can see from the challenge description, the .so file is added into some directory for python. Initially, I thought this was patching an existing file in python, however later on I realised that this is actually extending python. Basically, they are implementing a custom python module, but writing it in C using the CPython API.

Now if you read the link I linked above, you would know that when the module is imported, it will call the initialisation function that has the name PyInit_modulename. Thus we should first try to reverse this function, from what I understand, it’s equivalent to a main function or the init function in loadable kernel modules.

PyInit

PyObject *__cdecl PyInit_Collection()

{

if ( PyType_Ready((__int64)&CustomType) < 0 )

{

result = 0LL;

}

else

{

module = PyModule_Create2(&moduledef, 1013LL);

v1 = module;

if ( module )

{

++CustomType.ob_base.ob_base.ob_refcnt; // increase ref cnt

PyModule_AddObject(module, "Collection", &CustomType);

mprotect((void *)0x439000, 1uLL, 7);

v43968F = _mm_load_si128((const __m128i *)&xmmword_27E0);

v43969F = v43968F;

mprotect((void *)0x439000, 1uLL, 5);

init_sandbox();

}

result = v1;

}

return result;

}This function firstly initialises the custom type for this Collection type that will be implemented. All the configuration for this type is in the struct CustomType, which is a PyTypeObject struct with certain attributes set. In this case, the tp_new, tp_init and tp_methods are set. tp_new contains a pointer to a function that will allocate memory for each new Collection object, and tp_init will initialise the data in this newly allocated memory whenever a new object is created. tp_methods contains a pointer to an array of structures that define the methods this type will implement, in this case there is only get.

Afterwards, some weird shit is done with mprotect, I think they are patching out useful gadgets, but I’m not sure. Anyways, this didn’t matter later on for the solution. Then init_sandbox is called, which basically implements some seccomp protections. My teammate daniellimws was working on this challenge with me and reversed the following protections.

ALLOW:

exit

exit_group

brk

mmap

- arg[0] must be 0

- arg[2] must be 3

- arg[3] must be 0x22

- arg[4] must be 0xffffffff

- arg[5] must be 0

munmap

mremap

mreadv

futex

sigaltstack

close

rt_sigaction

write:

- only allow fd 1 and 2

So, we can’t jump to a one_gadget or call system(“/bin/sh”) since we can’t use execve. We’ll probably have to read the flag with readv and print it out with write.

tp_new and tp_init

The next functions to take note of would be the new and init functions, since they are the first ones called when initalising a new Collection object. Being someone who doesn’t like reverse engineering a lot, I kind of skimmed through these functions, which turned out to be my downfall later on (missed the intended vuln). In summary, tp_new checks if you initalised the object with a dictionary, and ensures that the dictionary only has 32 or less members.

a = Collection.Collection({"a":1337, "b":["dab"], "c":{"d":"lmao"}}) # legal

b = Collection.Collection(1337) # illegaltp_init will ensure that all members are only of type Long, List or Dict. Afterwards, it creates a sort of linked list of the keys of the members and the type of the member. This reminds me a lot of the shape concept that they use for defining objects in some javascript engine (I forgot which). The shape will look something like this.

If the object is: a = Collection.Collection({"a":1337, "b":["dab"]})

shape looks like:

Shape -> List-head -> Node(a)-record -> Record -key -> "a"

-type = 1(long)

-next -> Node(b)

-tail

|

|___> Node(b)-record -> Record -key -> "b"

-type = 0(list)

-next -> NULL

Sorry if this diagram is confusing, but it’s a bit hard to explain. To understand my exploit you don’t need to understand this concept too deeply, so yeah. Another additional note though, if you create 2 Collections and they share the same type of members (same number of members, same names, same types), the old Shape will be reused, and a new Shape will not be created. This turns out to be important for the intended vuln.

Collection struct

Now the Collection type is implemented as a Python object, so it will follow the Python object convention, which states that every object will start with 2 fields, ob_refcnt and ob_type. ob_refcnt is the reference counter for the object. This is important as it determines whether the object will be cleared by the garbage collector.

a = "dab" # now "dab".ob_refcnt = n

b = a # now "dab".ob_refcnt = n+1When there are no more references to the “dab” object (no more variables in scope refer to this object), ob_refcnt will drop to 0 and the Python garbage collector will clear up this object in memory, so that a following allocation can use this space again.

ob_type just points to the PyTypeObject for this particular object, so that Python will know all of it’s properties like functions that it can call, or its data elements etc. Other than these two default fields, our Collection struct has additional properties, and the object looks something like this in memory.

a = Collection.Collection({"a":1337, "b":["dab"], "c":{"d":"lmao"}})CollectionType for a^:

0x0 : ob_refcnt = 1 (or any value)

0x8 : ob_type -> CollectionType

0x10: shape -> the shape that describes this Collection

0x18: data0 = 1337 (for our example object)

...

get

This function can be called like so.

a = Collection.Collection({"a":1337, "b":["dab"], "c":{"d":"lmao"}}) # legal

print(a.get("a")) # will print 1337When you call .get("a"), the function will traverse through the shape of the Collection a, in order to determine the index and type of the data it is returning (data0…dataN). Something special about the Collection object however, is that it does not store every type the same. For Lists and Dicts, it will store a pointer to the corresponding List or Dict python object. On the other hand, for Longs, it will compute the value and store it as a long long value directly in the memory spot, rather than the usual way which stores a pointer to the Python Long object.

Vuln?

Now that we have a rough idea of how the module works. We tried to find the the vuln in the extension. After messing around for a while, we found a bug with how the Collection object handles the reference count of its members. Now if you recall from above, when you gain a reference to a Python object, you should increase the reference count of the corresponding object, this prevents the object from getting cleared by the Python garbage collector. However, what we found was that the get() function does not increase the ob_refcnt field for the member even though it is returning a new reference to this object. This would be okay if Python internally will increase the ob_refcnt, but it turns out this was not the case. Thus we could create a case where the ob_refcnt for the Collection’s members keeps dropping, even though the collection object still holds a reference to it.

a = Collection.Collection({"a":1337, "b":["dab"], "c":{"d":"lmao"}}) # ob_refcnt for the "a" object = n

a.get("a") # Since this doesn't assign to a variable, it will immediately go out of scope, Python will reduce ob_refcnt for the object

a.get("a") # ob_refcnt = n-2

a.get("a") # ob_refcnt = n-3

a.get("a") # ob_refcnt = n-4Eventually ob_refcnt hits 0, and the Python internal garbage collector will get to work, clearing up the object. This thus gives us a use-after-free vulnerability, as we can still access this garbage-collected object through a.get("a"). Now after we found this vulnerability, we went through many different attempts that all failed, wasting many hours. This writeup is already gonna get pretty long so I will go straight to the solution we found.

Collectionception

While we can’t put a Collection in a Collection, we can however put a Collection in a list that goes into another Collection. Now this may not seem very useful, but what daniellimws realised was that when a list is cleaned up, the ob_refcnt for all its elements will be reduced, so we could also free up the objects inside the list (like our Collection). Now, we essentially can control a Collection object after it’s been free’d! How do we exploit this?

how2pythonheap

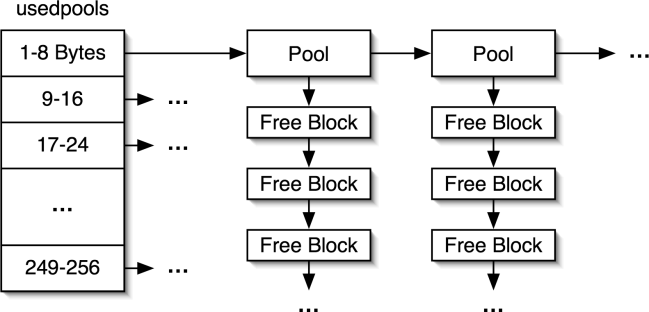

So far all the Python objects we have interacted with are allocated through Python’s internal object allocator, instead of the malloc or free that we are used to seeing in heap challenges. So naturally, it would be good to read up on the internal allocator called pymalloc, this will allow us to understand how to exploit this use-after-free that we have.(link) From the link, look at this line.

When a block is freed, it's inserted at the front of its pool's freeblock list.

Doesn’t that sound familiar? This is the same behaviour as glibc’s tcache or fastbins, which stores free’d chunks in a singly-linked list, with the most recently free’d chunk at the front of the list. And the best part is, AFAIK, there are no pesky security checks! Now let’s try to exploit this just like how we exploit fastbins or tcache chunks. If we have 2 chunks, A and B, where the garbage collector clears B followed by A. This is how the linked list will look like.

Doesn’t that sound familiar? This is the same behaviour as glibc’s tcache or fastbins, which stores free’d chunks in a singly-linked list, with the most recently free’d chunk at the front of the list. And the best part is, AFAIK, there are no pesky security checks! Now let’s try to exploit this just like how we exploit fastbins or tcache chunks. If we have 2 chunks, A and B, where the garbage collector clears B followed by A. This is how the linked list will look like.

Chunk freelist: A -> B -> NULL

Now when I create 2 new Collection objects, the allocator will allocate them address A followed by B.

If we have a use-after-free on A, we could potentially change this pointer (usually pointing to B) to another memory location we wish, allowing us to land a chunk at any arbitrary writeable location. But how do we control this pointer, even if we have a use-after-free with A? Earlier, we understood that the first member of every Python object is the ob_refcnt field (which is where the linked list pointer is located), and currently our use-after-free is with a Python object. How can we control the ob_refcnt field arbitrarily?

There is one way we can control the ob_refcnt, by making more references to object through assigning variables to this object. This limits us to only being able to increment the pointer, but this is good enough. In the end, my solution was to make many references to A, which increments the pointer such that the freelist looks like so.

Chunk freelist: A -> (B+0x130) -> ?

Now when we allocate new Collection objects, the first one will be located at address A. The next allocation however, will allocate the Collection object at address B+0x130, which I made it such that it will land in the data section of another existing Collection C! This overlapping situation enables us to control the data section of C through B, and when we access the data through c.get(), it will return it according to the rules defined by the shape of C. Therefore, we could write an arbitary address by writing a Long using B, while C would access this value thinking it is a pointer to an object, as it’s own shape does not think the value is a Long. I think this is called a type confusion (maybe).

oof

After this, I was stuck. Although now I could access arbitrary addresses as Python objects, I was not able to leverage this to create an arbitary read or write primitive. It was possible for me to control code execution by faking a Python object that has a new type implemented by me, then I could control execution through the function pointers of the type. However, this only gave me control of RIP, and I couldn’t control the other registers, neither could I control the rest of the execution. If I had a one-shot gadget, this challenge would be solved, but since there is seccomp in place, I couldn’t leverage this to solve the challenge. And this is as far as I got during the CTF.

Post-CTF

Now initially when I was trying to create an arbitrary write or read primtive, I tried making get() return a fake Python List Object I created in memory. I was hoping that this would grant me an arbitrary write through the List’s contents.

typedef struct {

PyObject_VAR_HEAD

/* Vector of pointers to list elements. list[0] is ob_item[0], etc. */

PyObject **ob_item;

/* ob_item contains space for 'allocated' elements. The number

* currently in use is ob_size.

* Invariants:

* 0 <= ob_size <= allocated

* len(list) == ob_size

* ob_item == NULL implies ob_size == allocated == 0

* list.sort() temporarily sets allocated to -1 to detect mutations.

*

* Items must normally not be NULL, except during construction when

* the list is not yet visible outside the function that builds it.

*/

Py_ssize_t allocated;

} PyListObject;Since this was my own fake object, I controlled ob_item, and I was hoping that I could set this to an address and write to it using .append() or []. However, this didn’t seem to work out in the end. After the CTF ended, I skimmed through the solution of the author, and found out the element I was missing. Rather than using a python List, he used this type called array.array. It has some similarities to a List, but the big thing about this type is that it’s contents are stored as C Types and not Python Objects! With this, an arbitrary read and write will be very easy.

typedef struct {

typedef struct arrayobject {

PyObject_VAR_HEAD

char *ob_item; // <- Make this point to the address you want to read/write

Py_ssize_t allocated;

const struct arraydescr *; // <- Make this point to "L" for long

PyObject *weakreflist;

int ob_exports;

} arrayobject;Make the two days of time worth it

After realising this, I stopped reading the intended exploit and tried to get my own exploit working. Just like before, I make the two Collections partially overlap each other, with them having different shapes. Thus I could write an address as a Long and return it as a Python object. Now I just craft a fake array.array object in memory, and make my collection return it to me. Since I control the ob_item field, I can write/read anywhere!

Now to finish up the exploit. I try to leak the stack address through this environ variable that is present in the python3.6 binary. I can then write a ROP chain very far down the stack (very high address), so that it won’t interfere with any stack frame that might cause a crash. In order to trigger the ROP chain, I calculate the address on stack for the saved RIP when the arbitrary write is being performed. This way, I can make the arbitrary write overwrite it’s own return address. In the return address, I placed a pivot gadget which runs very far down the stack add rsp, 0x9c0; pop rbx; ret;, all the way to my ROP chain! Now the ROP chain doesn’t need to be explained too much, based on server.py, the flag is currently opened at file descriptor 1023. So I can setup the structs needed for a readv syscall (allowed by seccomp), to read from fd 1023 to some random writable address. Then I can print this out with write! And thus, we get our flag, hours after the CTF ended T.T

35C3_l1st_equiv4lency_is_n0t_l15t_equ4l1ty

Summing Up

This year’s 35C3 CTF was mega hard, so many hard challenges like Browser exploits, VBox escape etc… And I couldn’t solve the easy one XD. But I still enjoyed the CTF though, learned a lot about CPython internals just from one challenge. And I think it’s quite cool to check my own progress, since 34C3 Junior CTF was either the 2nd or 3rd CTF I had tried, and at that point I was super happy having solved one of the bash escape challenges.

Btw, I’m not super happy with this writeup, but I don’t want it to get too long either, so if I missed out explaining some part just comment or smth.