This weekend I decided to play the RITSEC CTF. Considering it wasn’t too big a CTF, I decided to play alone to see how I can do outside of my usual comfort zone (not only working on pwn). I solved these following challenges, but I will only writeup a few challenges that stood out to me.

Pwn (all)

- ezpwn - Solves: 323, 100pts

- Gimme sum fud - Solves: 83, 100pts

- Yet Another HR Management Framework - Solves: 43, 250pts

Crypto

- Nobody uses the eggplant emoji - Solves: 72, 200pts

- Who drew on my program? - Solves: 117, 350pts

Web

- Space Force - Solves: 593, 100pts

- The Tangled Web - Solves: 455, 200pts

- Crazy Train - Solves: 83, 250pts

- What a cute dog! - Solves: 259, 350pts

Forensics

- Burn the candle on both ends - Solves: 222, 150pts

- I am a Stegosaurus - Solves: 368, 250pts

Misc

- Litness Test - Solves: 854, 1pts

- Talk to me - Solves: 597, 10pts

Writeups

Yet Another HR Management Framework (pwn)

Although there has been a ton of human resources management frameworks out there, fpasswd still wants to write his own framework. Check it out and SEE how that GOes!

nc fun.ritsec.club 1337

Author: fpasswd

This challenge was written in Go, a programming language designed by Google. I’ve never written Go code and I’ve only ever encountered it in CTF reversing or pwnable challenges. From what I’ve seen, its a pain in the ass to reverse. I solved the other GO pwn challenge Gimme sum fud only using dynamic analysis in gdb, and so I was hoping to be able to solve this challenge entirely with dynamic analysis too, saving me the effort of reading the decompiled code. In the end, it worked out, so I’m making this writeup to document some of the interesting things that could be helpful in the future.

Overview

Welcome to yet another human resources management framework!

============================================================

1. Create a new person

2. Edit a person

3. Print information about a person

4. Delete a person

5. This framework sucks, get me out of here!

After running the binary, you are presented with this menu. If you’ve played some CTF pwn challenges, this format of menu should be very familiar as most heap challenges are done using this format. Immediately, I can guess that malloc, and free are going to be called, or at least some variants of them like calloc etc. The easiest way to confirm this is to simply load the binary in gdb, and break * malloc. If it hits the break after choosing menu option 1, then we know that that option calls malloc in some way (it does).

Cap’n Hook

For heap challenges, it is important to understand when a chunk is malloc‘d, when it is free‘d, and the relevant sizes. If the function reads a string of size n, but the malloc chunk is smaller than n, then we can have an overflow. Seeing what chunks are freed will also give us a good idea of possible use-after-frees or other similar vulnerabilities. So the first thing I wanted to do was to hook the malloc and free functions to know when they are called. I tried three different approaches.

- heap-analysis-helper

- LD_PRELOAD

- GDB <3

Firstly, heap-analysis-helper. This is a command in the gdb extension that I mainly use, gef. When you run this command, it should print out whenever malloc and free are called, with their relevant returns and arguments. However, when I tried to use it for this binary, it seemed to not work. I have a feeling this might have to do the multiple threads and stuff. Anyways, since I didn’t know how this is implemented, I couldn’t find a fix so I just scrapped the idea.

Secondly, I tried using LD_PRELOAD. LD_PRELOAD is an environment variable that describes the path of other shared binaries that should be loaded before execution. Following something like this example, you can hook any functions to show debug output. I think I’m dumb or something because I couldn’t get it to work, but anyways no biggie.

Lastly, I used GDB, with a gdbscript. This is basically just writing gdb commands in a script to automate some gdb actions easier. I like using gdbscripts very much and I always use them to help improve my workflow if it is possible. In this case, I simply used breakpoints and printf instructions (never knew gdb could printf before this) in order to show debug output for each call to malloc and free. Here is a snippet of the gdbscript to hook free.

b * 0x8048f30 #free@PLT

commands 2

silent

printf "free(%p)\n", *(unsigned int*)($sp+4)

c

end

Now every time malloc or free is called, I can see debug output, knowing their return values and arguments supplied.

Welcome to yet another human resources management framework!

============================================================

1. Create a new person

2. Edit a person

3. Print information about a person

4. Delete a person

5. This framework sucks, get me out of here!

Enter your choice: 1

Creating a new person...

[Switching to Thread 0xf7dde700 (LWP 12627)]

malloc(12) #_cgo_df1ab1e22195_Cfunc_createPerson ()

= 0x81a8008

Enter name length: 1337

malloc(1337) #x_cgo_malloc ()

= 0x81a81e0

Enter person's name: NAME

Enter person's age: 12

// I couldn't seem to silence the output of the "finish" command, hence the weird x_cgo...

Plunder.py

With these debug hooks, you can just explore the binary. Within no time, it’s very easy to identify the exploit (maybe I could have done static analysis and found it but nvm lol). When you edit an entry, no call to malloc or free is made, even when you specify a larger size. This could mean that realloc is called, OR that it does not care about the old size. It turned out to be the latter so it’s a heap overflow vulnerability.

Editting a person...

Enter person's index (0-based): 0

Enter new name length: 133700 # original chunk is size 1337

Enter the new name: OVERFLOW

If you noticed earlier when “Creating a new person”, a malloc(12) call is made. This indicates that there is some metadata for a person saved on the stack, probably a pointer to the name. Just set the age to an easily searchable size like 0xdeadbeef, and search for that value in gdb. Exploitation becomes very obvious and easy after this point, as the person metadata looks like this.

0x081a8008│+0x0000: 0x080ebb10 → <printPerson+0> push esi

0x081a800c│+0x0004: 0x081a81e0 → "NAME"

0x081a8010│+0x0008: 0xdeadbeef

We have a function pointer and a string pointer in the heap, we can just overwrite these with our heap overflow and perform the usual, leak libc -> system(“/bin/sh”) exploit sequence.

0x081a8008│+0x0000: 0x080ebb10 → <printPerson+0> push esi

0x081a800c│+0x0004: 0x08191028 → 0xf7e4e470 → <free+0> push ebx

0x081a8010│+0x0008: 0xdeadbeef

By overwriting the name pointer with the GOT address of free, we leak a libc address when we print a person with option 3. We can thus calculate the base address of libc from this leak.

0x081a8008│+0x0004: 0xf7e10940 → <system+0> sub esp, 0xc

0x081a800c│+0x0008: ";/bin/sh;"

0x081a8010│+0x000c: "n/sh;"

Now we can pop a shell by setting up a person like this. This will result in the binary calling system("\x40\x09\xe1\xf7;/bin/sh;") when you print the person. Although the first part is not a proper shell command, it will end at the semicolon and our proper “/bin/sh” execution will run.

Just one note, the fastbins seemed to change a bit here and there, so I just created 3 people at the start of my exploit as padding, this will most likely clear the fastbin list and so my exploit will be more stable. I won’t go further into the exploitation of this binary as my focus was more on the dynamic analysis aspect, if you do not understand my exploit code, you can leave a comment or just ask on the CTF Discord (there are quite a few solvers).

RITSEC{g0_1s_N0T_4lw4y5_7he_w4y_2_g0}

Who drew on my program? (crypto)

I don’t remember what my IV was I used for encryption and then someone painted over my code :(. Hopefully somebody else wrote it down!

Author: sandw1ch

So if you’ve read my blog, you would know that I’m a pwn guy, and I rarely ever do crypto (just coz I don’t know much crypto). Recently I’ve been reading up on some crypto stuff and only just learnt about block ciphers. Since this challenge was of a high point value with many solves, I thought it would be a good opportunity to apply my new knowledge.

Overview

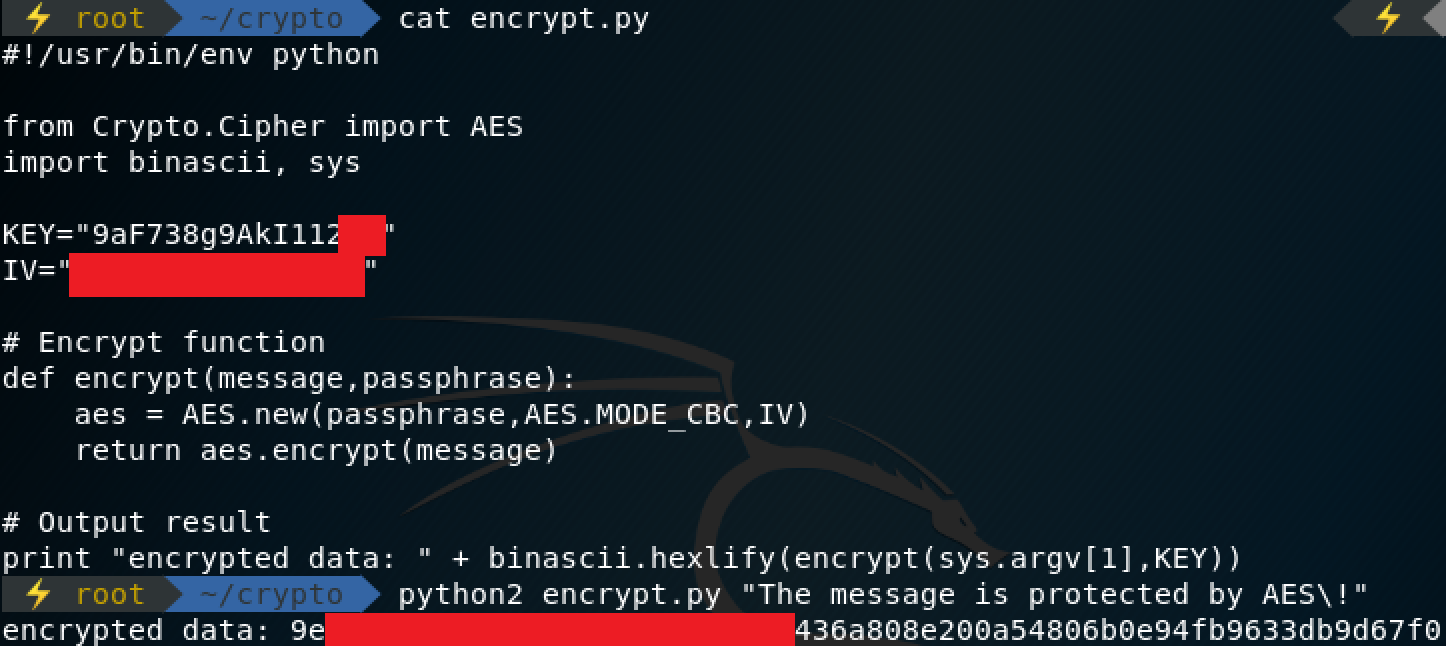

In this challenge, we are provided with only one image, a screenshot of a encryption script and one run of it.

As you can see, some of the key and the encrypted output is covered, and the IV is completely unknown. From the challenge description, we are supposed to determine the IV to get the flag. The first thing to do is transcribe what we know of this script into a python script, putting placeholders for the values we don’t know. After transcribing, you can easily figure out how many characters of the KEY is unknown. We know 14 bytes of it, and the block size should be some multiple of 8, so it’s quite obvious (can tell from the size of the red block too), that two bytes are missing from the key. Two bytes is a very small amount, it will only take 256^2 (65536) tries to bruteforce it. So now we have some known values, the PLAINTEXT, maybe the KEY (bruteforce), and some of the expected CIPHERTEXT.

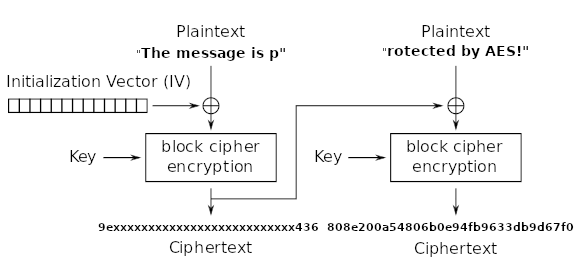

This is shown in the above diagram. From this diagram, we can see a way to recover the key. If we know that

encrypt( "rotected by AES!" xor 9e...436a, key) = 808e200a54806b0e94fb9633db9d67f0

Then we can recover the key by doing a simple rearrangement of this equation.

decrypt( encrypt( "rotected by AES!" xor 9e...436a, key), key ) = decrypt( 808e200a54806b0e94fb9633db9d67f0, key )

therefore

("rotected by AES!" xor 9e...436a) = decrypt( 808e200a54806b0e94fb9633db9d67f0, key )

Now that we have formed the above equation, we can decrypt the second block of the ciphertext, using different keys (bruteforce 2 unknown bytes). This decrypted result when xor’d with the string “rotected by AES!” should start with 9e and end with 436a(in hex notation). Therefore, we can just keep bruteforcing till we find a key that fulfils this criteria. This can be done ECB decryption instead, doing the xor ourselves afterwards. From this, we can recover the original key.

key = 9aF738g9AkI112#g

Now that we know the key, we can work backwards to find the IV using the same principle as before when recovering the key, except that now no bruteforce is required.

find cipher block[0]

block[1] = e( block[0] ^ plain[1] )

d( block[1] ) = block[0] ^ plain[1]

block[0] = d( block[1] ) ^ plain[1]

find iv

block[0] = e( iv ^ plain[0] )

d( block[0] ) = iv ^ plain[0]

iv = d( block[0] ) ^ plain[0]

Just put this all in a solve script and we get the IV! (which turns out to be the flag).

RITSEC{b4dcbc#g}

Overall about the CTF

Playing this CTF alone was quite fun, so I think I’ll do this once in a while when a smaller CTF comes out. Also I finished 69th which is quite amusing for my sense of humour :P.

Just a note if any orgs read this, I’m not sure if there was any reason for using static point values for your CTF, but I strongly suggest against using that in the future. There were quite a few challenges that had higher point values, and yet a lot more solves than challenges with low point values. This makes it quite weird since some challenges may be really difficult to solve and yet only give 100 points, but others that turn out to be a lot easier give a lot more points. It’s probably better to use dynamic point values like many other CTFs. Other than that, I still enjoyed the challenges.

Just a note if any orgs read this, I’m not sure if there was any reason for using static point values for your CTF, but I strongly suggest against using that in the future. There were quite a few challenges that had higher point values, and yet a lot more solves than challenges with low point values. This makes it quite weird since some challenges may be really difficult to solve and yet only give 100 points, but others that turn out to be a lot easier give a lot more points. It’s probably better to use dynamic point values like many other CTFs. Other than that, I still enjoyed the challenges.