Hello Neighbor!

nc neighbor.chal.ctf.westerns.tokyo 37565 (Solves: 37, 239 pts)

Disclaimer: I didn’t manage to solve this during the CTF because of a logic error (which I explain below), but I thought I’ll write this anyways.

This challenge has a very small binary (6kb, my exploit code is half the size). And it only revolves around 1 function, which I named get_format. The code looks like this:

void __fastcall __noreturn get_format(FILE *stream) // the stream passed was STDERR

{

while ( fgets(format, 256, stdin) )

{

fprintf(stream, format);

sleep(1u);

}

exit(1);

}Issues

At first glance, this is quite obviously vulnerable to a format string attack, because user-controlled input is being used as the format string in the fprintf call. Normally, this would be a very straightforward attack, however there are two issues that we encounter. Firstly, the buffer we are able to write our input in is not present on the stack, rather it’s in a global buffer in the bss section, this would mean that we won’t be able to write addresses and access them on the stack using %<index><fmt specifier> syntax. Secondly, the result of the fprintf call is sent to the STDERR FILE. This issue might not be evident when running the exploit locally as you will still see your output appear on the screen, but in the remote connection, only STDOUT is sent back to the user, while STDERR doesn’t get sent to the user. Thus we will be unable to leak any data back to ourselves to calculate any offsets(the binary is PIE so we can’t even use bss).

I Can See… I CAN FIGHT

Without knowing any addresses(PIE base, libc, stack), I won’t be able to do much even if I have this format string vulnerability. So the first thing we have to do is to find some way to relay program output back to ourselves. I had two ideas for this.

1) Overwrite the FILE pointer on the stack

If you check out the disassembly of the program, before each call to fprintf, it loads the first argument from an offset [rbp+0x8] from stack, which is the FILE pointer for STDERR. If we could somehow overwrite this FILE pointer to point to STDOUT instead, fprintf would start writing to the STDOUT, which we will be able to see. So I check out the addresses of the different FILEs.

gef➤ deref 0x000000000201020+0x0000555555554000

0x0000555555755020│+0x00: 0x00007ffff7dd2600 → 0x00000000fbad2887 <stdout

0x0000555555755028│+0x08: 0x0000000000000000

0x0000555555755030│+0x10: 0x00007ffff7dd18c0 → 0x00000000fbad208b <stdin

0x0000555555755038│+0x18: 0x0000000000000000

0x0000555555755040│+0x20: 0x00007ffff7dd2520 → 0x00000000fbad2887 <stderr

0x0000555555755048│+0x28: 0x0000000000000000

If we want to change the address of STDERR 0x00007ffff7dd2520, we will need to change the two least significant bytes 0x2520 to 0x2600, this doesn’t seem to difficult. However, we must remember that because of ASLR, these FILE structures (which come together with the libc), will be loaded at different address bases everytime. The last 3 nibbles (1.5 bytes) will remain the same, but if we change 2 bytes, that would mean that we only have a 1/16 chance of getting the last nibble correct. This chance isn’t too bad, so this method might be possible.

2) Overwrite the FILE structure itself

Rather than overwriting the FILE pointer on the stack to make it point to another structure for STDOUT, we could actually overwrite an important portion of the STDERR file structure which would allow us to recieve the input. To understand this technique, you must first understand that the FILE structure is just a wrapper that adds additional features for interacting with file descriptors. In the end, it still does contain the file descriptors it writes to, if we could change the file descriptor in the STDERR FILE structure to the file descriptor of STDOUT(1), we would be able to see output written to the STDERR FILE. You can check it out in the glibc source code.

struct _IO_FILE

{

// [redacted]

int _fileno; <-- Lets change this

// [redacted]

};You can see it in memory here.

gef➤ deref 0x00007ffff7dd2520 30

0x00007ffff7dd2520│+0x00: 0x00000000fbad2887 <start of FILE structure

...

0x00007ffff7dd2590│+0x70: 0x0000000000000002 <file descriptor (2 for STDERR)

...

If you notice, the address of the file desciptor member only has the least significant byte different from the address of the start of the FILE start. Therefore, if we overwrite only the least significant bit of the FILE pointer on the stack (from 0x20 to 0x90), and then we write 0x1 to that pointer, we would be able to start seeing output as writing to the STDERR FILE stream would actually write to our STDOUT file descriptor. Since we only have to overwrite the least significant bit (that will always be constant across executions), this will work everytime, as compared to method 1 which only works 1/16 of the time.

How do we actually write?

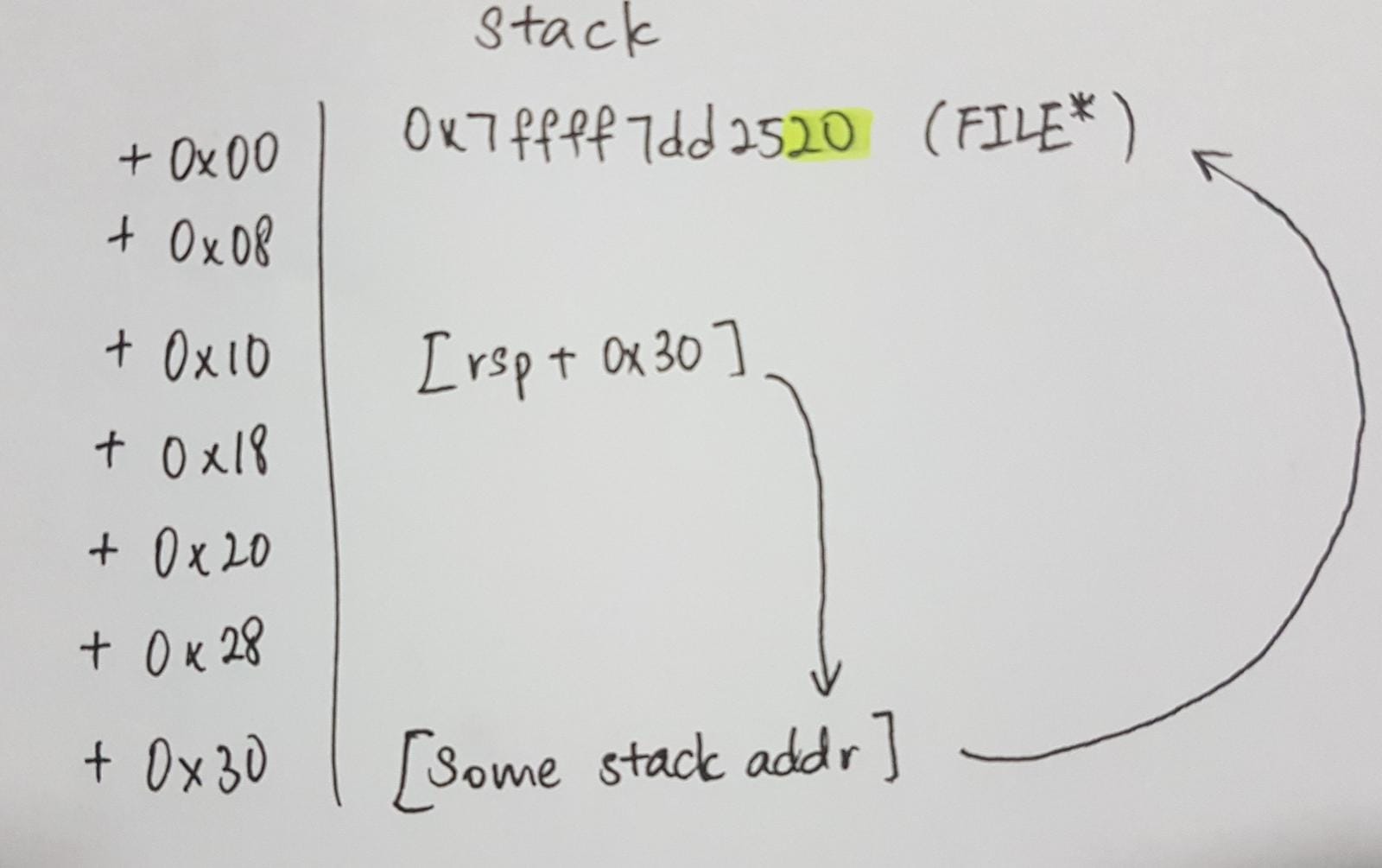

So far I’ve been talking a lot about writing, but as I’ve mentioned earlier, we do not know any addresses and we cannot write addresses to the stack with our fgets call. In order to solve this, we rely on partial overwrites to do something like a “two-stage” write. To understand this technique, let’s check out the stack while we are in the get_format function.

0x00007fffffffd9a0│+0x00: 0x00007ffff7dd2520 → 0x00000000fbad2887 ← $rsp

0x00007fffffffd9a8│+0x08: 0x00007ffff7dd2520 //nt impt atm

0x00007fffffffd9b0│+0x10: 0x00007fffffffd9d0 → → → → → → → → → → →

0x00007fffffffd9b8│+0x18: 0x00007ffff7dd2520 //nt impt atm |

0x00007fffffffd9c0│+0x20: 0x00007fffffffd9d0 //nt impt atm |

0x00007fffffffd9c8│+0x28: 0x0000555555554962 //nt impt atm |

0x00007fffffffd9d0│+0x30: 0x00007fffffffd9e0 ← ← ← ← ← ← ← ← ← ← ←

At [rsp+0x10] in the stack, we have a pointer pointing to an address in the stack that contains another stack pointer. Since these addresses are quite close, if we overwrite the least significant byte of the pointer at [rsp+0x30] using the pointer we have at [rsp+0x10] we will be able to control this pointer. Thus this pointer at [rsp+0x30] acts like our cursor. Once we’ve moved our cursor to the correct address we want, we can just write using our pointer as the address and write to a stack address. However, stack addresses will be more random than other addresses like libc addresses as differences in environment variables will change even the least significant byte (last nibble should remain the same though). So we have to bruteforce this a bit, moving our cursor from the lowest address (LSB is 0x00) to the highest possible (LSB is 0xf0). We go from low to high as our important pointer at [rsp+0x10] also has it’s last nibble set as 0, so if we go from high to low addresses, we would overwrite our pointer at [rsp+0x10] even before we overwrite the FILE pointer at [rsp+0x00]. After we try one address, we write to the FILE pointer and hope that we overwrite the file descriptor. If we recieve input back from the server, we are successful and we can stop bruteforcing. Here’s a diagram that might provide a better (or worse) illustration of the idea.

Control execution

Now if we’ve succeeded up till here, we would be able to leak the PIE base, the libc base, and even the stack addresses if we wanted. With all this information, it would be easy to calculate the address of a one_gadget. Then we could possibly write that one_gadget to a Global Offset Table entry. However, writing to the GOT won’t actually work in this case as the binary has FULL RELRO, which makes the GOT read-only. The solution requires a cool trick. In libc, there are these things called hooks which are function pointers in memory that get called whenever the relevant function is called. A hook like the __malloc_hook would be (obviously) called whenever we make a call to malloc. And this is the exact hook we use for our case. But how would we call malloc? It turns out, if you call printf (or its variants) with a very large string, it would call malloc (to hold its buffer or something I’m not too sure). Therefore, we can enter something like %70555x which would try to print a very very large string, forcing a call to malloc. I don’t want to explain too much about how to write to __malloc_hook as the idea is very similar to our previous strategy to overwrite the FILE pointer, just use an address as a cursor that you move around to write byte-by-byte to the stack. Additionally, since we have a stack leak, we can write with precision (no need to bruteforce anything).

My fatal error

So with everything up till here the exploit should work and we should get a shell in the remote server easily (although the script is kinda slow). But I was unable to get the exploit to work during the CTF because of one line of code. For the first part of the solution, you may recall that we need to bruteforce the least significant byte, and that we need to stop exactly when we hit the correct address as the next write would overwrite the stack pointer that we wish to use in the future. However, in my inital script, after each write, I immediately checked whether the server sent any output to myself. This was the general idea.

while True:

# try to overwrite the file descriptor

# Did the server return any output to me? -- No --> (Go back and try again)

---- Yes---> Break

I was hoping that the format strings I sent it to do my file descriptor writes would be sent back to me right after I fix the file descriptor. However, what happened was that right after I’ve changed the file descriptor, I did not provide any input for the server to reply back to me, my previous inputs were all already sent to the original STDERR. What I should have done was.

while True:

# try to overwrite the file descriptor

r.sendline("I'm so dumb")

# Did the server return any output to me? -- No --> (Go back and try again)

---- Yes---> Break

This way, the server would return me “I’m so dumb” immediately after I have succesfully altered the file descriptor. Without that line, I had an “off-by-one” error, which caused me to overwrite the stack pointer I was using on the stack for my future writes, causing segfaults. I only realised this error a few hours after the end of the CTF T~T.

TWCTF{You_understand_FILE_structure_well!1!1}